There is no denying that forest fires are a reality in the American West and across the globe. Inevitably those miles of burned forest will affect the trails we used to recreate. I recently got an email from a friend with some statistics about fires.

He mapped out how many miles of the OTT has been burnt since 2017. It's about 131 miles or 20% of the whole route. 38 of those were just this past year in the Cedar Creek Fire. Below is a screen shot from a CalTopo map that shows where fires have occurred since 2017 (year one of the OTT) The blue line is the current alignment of the Oregon Timber Trail. Fires are orange and red. Not to downplay the mileage, but this map doesn’t give us any detail about burn severity, just fire perimeters.

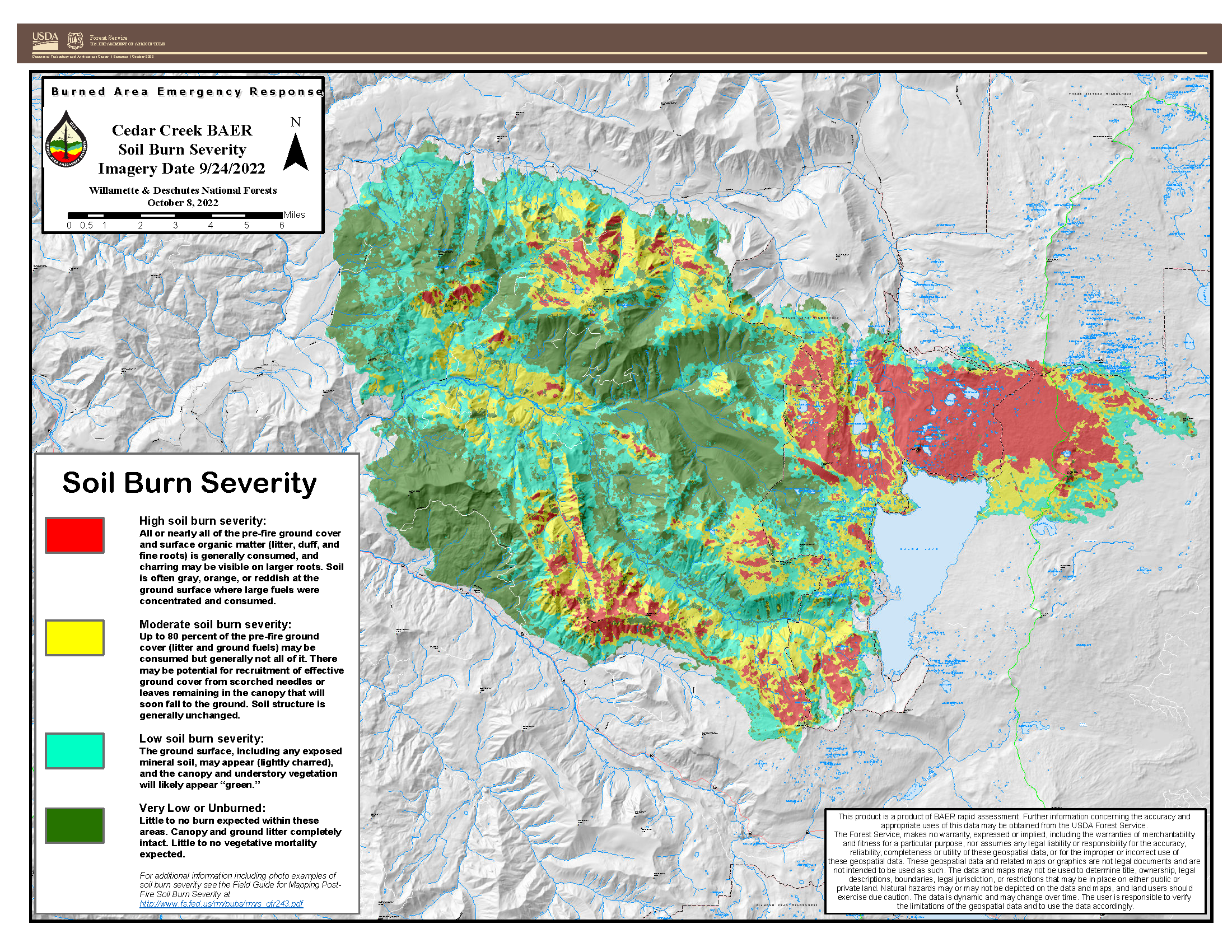

That got me thinking about the Oregon Timber Trail’s plans for 2023, which will likely include starting on the Cedar Creek fire rehab. Of course it’s a process that requires getting approval to enter the area to begin the work. Once that happens, we’ll start the rehab process. Upon approval to enter the area, we’ll get back to our work on the Fugrass connector. Here is a note from Kevin Rowell, who recently complete the B.A.R.C. (Burned Area Reflectance Classification) post-fire evaluation process. As usual, Kevin gives some great perspective and reminds us that there are varying levels of severity and only parts were high severity burn.

Kevin Rowell

“There are probably 38 or so miles of OTT inside the Cedar Creek perimeter, but that does not translate to 38 miles of burned trail. On the Bunchgrass Trail from Fuji to Little Bunchgrass, there are about 8-10 miles of affected trail. On Waldo Lake, there are about 8 miles affected, all on the west side. There are roughly another 5 miles affected east of the Waldo basin on the Deschutes. That is along the Met-Win or that general area.

This is a Soil Burn Severity map from the Cedar Creek fire. The legend explains what to expect for each color. The high burn severity is most concentrated on the north end of Waldo Lake and includes Bunchgrass Ride and Fuji mountain.

“The first thing that needs to happen is an assessment of each area we need to work on. I will do that as soon as the snow melts and I can get there in spring. I will report that info to the District Ranger and write a Risk Assessment. Once the Ranger approves that, we can start doing work.”

I was then reminded of Nathan Pipenberg’s excellent article that was published in October of 2021. Nathan was a former wildland fire fighter and author that joined us for a Watson Fire stewardship event. He provides some great perspective, rooted in reality and inspired by the OTTA and volunteers work ethic. Nathan reminds us of the importance of the drive to do the work, and the collective strength of volunteers that return year after year to rehabilitate and do the work.

Who says rehabbing burn zones is no fun? Adam Craig taking the fun line at the end of a long day of Watson Fire rehab.

“Trial by Fire” (Mountain Flyer 70)

by Nathan Pipenberg

“The final calamity on display was the swath of land surrounding the campground itself, where stands of lodgepole pines stood debarked and dying, despite being untouched by fire. This was my first glimpse of the Fremont-Winema National Forest’s “red zone,” where mountain pine beetles have chewed through some 300,000 acres of lodgepole forest, leaving a sea of ghastly gray timber in their wake. This expanse of dead trees, by nature drier than living ones, helped drive the explosive fires through the landscape I’d recently passed.

As I parked my car and began to meet the other volunteers gathered for the stewardship event, I felt a sense of dejection despite all of the friendly introductions. As a former wildland firefighter, I’ve spent weeks battling a single fire, stationed in fire camps that can balloon to over 1,000 personnel. During those kinds of fires, there’s no magic number of firefighters that can turn the tide. Battle lines are drawn in the morning and erased by noon; the fire progresses, and crews retreat like clockwork. The process repeats the following day and the day after until you’re finally sent home and another crew replaces yours. I couldn’t help but wonder if this weekend of trail work would feel like those fire assignments. Like a battle we were never going to win.”

“After just one day on the job, I realized that my pessimism had been blunted by the strange, addictive momentum that trail work instills.

My 100-foot section connected to another, then another, and by the end of the day a trail etched through the ground. As we walked back to the vehicles we talked about the trail we’d be tackling the next day, and how good it would feel to wash away the dirt with a dip in the lake. Beneath a balm of sweat and purpose, the charred landscape faded. That’s when I realized this story isn’t about wildfire, at least not entirely. The burn scars, the trail closures, the looming specter of even more severe fire seasons to come—those are all undeniable truths that the American West will grapple with for years to come.

But this story is really about momentum and how it’s created. It’s momentum that allowed the OTT to develop in the first place. It’s what motivates volunteers to show up on holiday weekends to dig in the dirt. It’s what makes each hard-earned mile of trail carved into an unforgiving landscape a worthy goal. When the next wildfire comes, it’s momentum that will ensure the trail is here to stay.”

There’s plenty of evidence that mountain biking can serve as an economic engine in Oregon. In Oakridge, a town of about 3,000 where the timber industry once dominated the economy, recreation is helping to cover the gaps. A 2014 study found that mountain bikers spent between $2.4 to $4.9 million in Oakridge every year, accounting for about five percent of the town’s economy.

At the stewardship event, I met Thom Batty, who believes a similar revitalization could soon be underway in Lakeview, which serves as the southernmost trail town, or gateway community, along the OTT.

Batty moved from Portland to open Tall Town Bike & Camp, Lakeview’s first bike shop, in 2018. While it may seem odd to move away from a bike-crazed metropolis to start a bike business, Batty thought it made a certain kind of sense.”

2023 will be full of fire rehab work. We have plans to log out the worst sections of Crane Mountain in the Fremont National Forest. Crane mountain is known for it’s beetle kill blowdown and has been reported by many Timber Trail riders. Upon approval, we’ll venture into the Cedar Creek zone and start work on Bunchgrass, Fuji, and Waldo. The only way forward is to keep doing the work and bringing these trails affected by fire back to life. We’ll haul chainsaws miles in the backcountry, clear trail, cut down hazard trees and bring the tread back. In many cases, these miles of neglected trail will be better than ever. As Nathan Pipenberg so elequently said in his article, “When the next wildfire comes, it’s momentum that will ensure the trail is here to stay.” Help us keep up that momentum by donating today and keep an eye on our 2023 stewardship events, which will be announced in the spring.